Ian Ellingham + Corinivm-Peregrini Media

Micro Conservation

INHERITING A NICHOLSON & MACBETH GATE: A CASE STUDY IN MICRO-CONSERVATION

Ian Ellingham, MBA, PhD, OAA, FRAIC

Making decisions about heritage buildings is rarely easy – especially when the building is your own. It involves balancing seemingly endless competing factors. A couple of years ago, a curious adventure in micro-heritage unfolded on me.

Through the roaring twenties, Arthur Nicholson and Robert Ian Macbeth had a very busy practice in the Niagara area, and Macbeth’s successor firm remained active until recently. Indeed, on several occasions I was involved in managing projects designed by the firm - and Macbeth’s dour portrait still presided over the board room.

Nicholson and Macbeth were prolific, but they are best remembered for their houses. Most people call them “Arts & Crafts,” and they do align with that philosophy, but it is important to remember that the “Arts and Crafts” is primarily just that – a philosophy – not a style, and Nicholson and Macbeth interpreted it within the unique geographic and cultural context of Niagara. One of the characteristics of these houses is that many were designed to appear considerably smaller than they actually are – a refreshing contrast to today’s monster houses. Sometimes a group of houses appears together as a continuous streetscape.

The details can be fascinating. Many houses feature nubbly brick. Plaster mouldings and interesting millwork appear in the larger houses. One has a complex staircase worthy of Harry Potter’s school. Many houses feature decorative glass, as did many of the buildings Macbeth’s father built in and around Inverness, Scotland. Surviving original bathrooms feature elegant pastel tiles, but unfortunately, many have been ripped out in favour of more stylish avocado fittings. Amazingly, a small amount of flare was built into the roof ridge of some houses; few architects or owners choose to build the appearance of a sagging roof into their new buildings, but it does give them a very traditional feel.

Some of the most cost-effective special details were the side gates. They would have served, for the larger houses, to admit the milkman, breadman, servants and tradesmen. Although made from inexpensive softwood, they have actually been “designed.” The wonder is that so many survive. But most of the owners of these houses, except through the 1950s and 1960s, have been aware that they have something special.

As you may have guessed by now, a few years ago, my wife and I bought one of these houses. It has a chequered past. It was built in at least three phases as the original owner acquired the money, and the daughters and servants to fill it. For a time in the 1960s, it was divided into apartments – at a time when it was expected that older neighbourhoods would soon be cleared, and replaced with modern-as-tomorrow highrises.

The decaying gate to our secondary entrance was obviously not original, and I had resolved to measure one of the other [?] gates and make a reproduction. But one day, I noticed that the owner of a Nicholson & Macbeth house down the street had his gate in his driveway and was working on it. He said that his gate was well rotted, and he was building a copy, this time in oak, to match his garage and front doors. He lamented that the large metal strap hinges that once adorned the gate were missing. Presumably someone had modernized the gate at some point. I asked if I could measure it, but he gave it to me. It saved him a trip to the dump. With mixed emotions I took it home.

I soon found that having this gate is like being haunted by a whole heritage building. In some ways it is not really that old, and the materials are ordinary, but there is something special about it. It sat on the back deck for a year or so as a object for reflection.

It was badly rotted, and the further one looked, the worse the rot. One side had been protected by a roof overhang, but the top inch or so of the other side had disappeared. Various attempts to prolong the life of the gate had been made, so big nails had been driven through the frame and bent over, the frame being too rotten to hold nails in the usual way. Perhaps worst of all, the top finial was missing. It was easy to see why the previous owner had decided to built a replica. The shadows of the house numbers were there, together with the indications of some sign, perhaps announcing the tradesman’s entrance or the presence of a nasty dog. While now a light brown to match the rest of the house, the gate, and probably the whole house, was at some point light grey. Evidence of the original hardware could be seen. Was the handle a custom-made Nicholson & Macbeth item, or just a stock latch from the builder’s yard?

TAKING ACTION

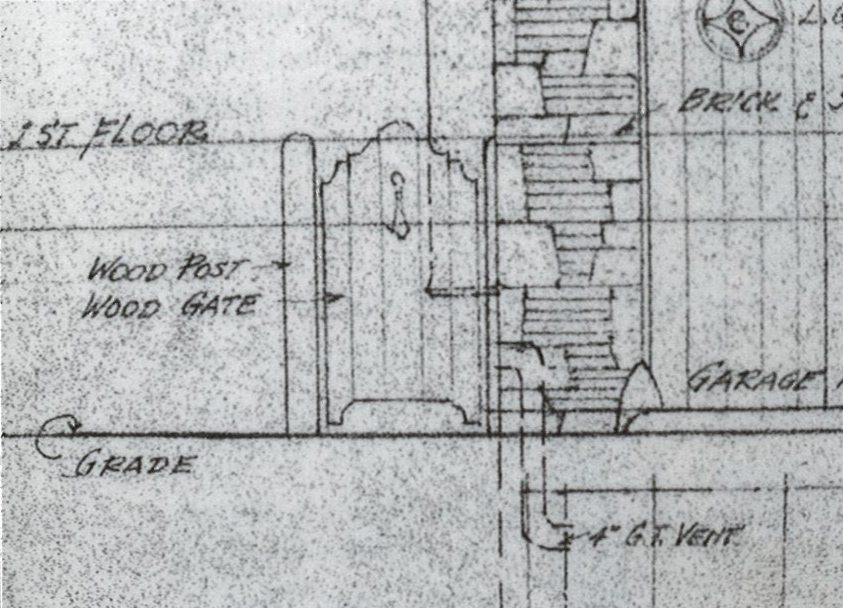

What exactly should one do in this situation? Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada offers a number of ideas. I started by photographing the gate, including the bent-over nails. The project not being urgent, I could indulge in some research. The delight is that many wonderful Nicholson and Macbeth drawings survive. Surprisingly, the elevation for the house down the street shows the gate – and there are quite a few differences between the drawing and the gate as built. While the bottom boards are essentially as drawn, and there is the keyhole sort of cut in the centre board (albeit the other way up), the top is quite different. The scrolls on the top of the end boards are not on the drawings, and the centre, as built, was obviously more fanciful than that shown. What happened? Did Nicholson & Macbeth give considerable latitude to the carpenter? Nicholson & Macbeth houses often show the hand of the same skilled trades. But somehow the gate, as built, does not exude the same cool design sophistication to be seen on the drawing and in other gates. It is more likely the work of an enthusiastic carpenter who started with the drawing and then did a free interpretation. We will probably never know. I have an image of Macbeth appearing at the site, pulling at his hair (he ended up quite bald), but ultimately worrying about some more important matter.

SO WHAT SHOULD ONE DO?

Not only was there a heritage quandary, there was a design issue as well. Perhaps my original strategy was best – copying one of the others, either exactly as it was originally or using more modern materials. Of course, it was possible to do nothing, deferring any action, while further thought was given and the old gate rotted into oblivion. It might have been donated to the local museum, but one might wonder if it would be a generous contribution to the cultural life of Niagara, or a silly prank to play on the museum.

Alternatively, it could be carefully reconstructed to be indistinguishable from the way it was when new. Or it might be partially restored to make it appear as it did originally, but take advantage of new materials and techniques. After all it is part of a real, functioning house, not of national significance, and people do push garbage cans and bicycles through it.

Some questions need consideration.

1. To what extent is the original building fabric important?

Should we try to keep the very molecules of the original gate, even though it is constructed of rather pedestrian softwood?

2. What aspects of the design are important?

If we believe that something about the gate is important, and if it is not the ordinary machined spruce, we must believe that the design matters. This suggests that we might be better to use a design actually developed by the architects.

But what part of the design is important? The boards in the gate were bevelled and grooved, and originally had wood splines between the boards. Is that important? Perhaps the bevels are, because they emphasize the individual boards, but the spline detail was probably the first part of the gate to rot away. It would seem inappropriate to keep a poor detail that is unnoticeable, and would probably fail again.

3. How do we deal with technologies we have available now?

Part of the reason the gate rotted was that water entered the exposed end-grain of the wood. If we wanted to make a long-lived gate, we would try to seal the ends of the boards better. We have better materials now. Moreover the gate sagged badly, even though it was cross-braced. Now we have prefabricated steel corner bracing for gates. What about them?

4. What about today’s design constraints?

This doesn’t seem to be one of the issues surrounding my gate, perhaps because the world of gates is rather unchanging. Gates do what they did in ancient Mesopotamia: they swing back and forth and let some people and animals through, and keep others out.

One of the things about dealing with the larger Nicholson & Macbeth houses is that they were designed with the assumption that there would always be servants. Now, no matter how hard one pushes the call-buttons, the servants never come. Buildings are long-lived assets, and they should probably meet the demands of ever-changing times. Hence, unless we are creating museums of past life-styles, they have to change.

5. How ‘Perfect’ do we want it to be?

Even the best parts of the gate exhibited eighty years of wear. If the boards were to be retained, substantial repair would be required. Where does one stop? Does one fill in all the minor nicks and knocks? If we repaired everything, it would appear as a completely ‘new’ gate, so why not just use new wood? And, of course, this is in a house that originally incorporated characteristics to make it look used (rather like pre-ripped jeans).

Personally, I feel it is inappropriate to try to make obviously old things look new. However, from marketing a renovated building in Toronto a couple of years ago, I found that most people in that case really wanted everything to be as-new. So, who is right, the market? Or some notion of “proper” heritage?

6. Can we pass on the information about its original form?

The heritage community believes in the value of information. The fact that I could find the drawings that related to the gate in its original location does help in dealing with it. Should we preserve the information about the original gate colour, or the nature of the original frame, or that it came from another house? I have some wonderful drawings of a Toronto building from the 1920s. What should I do with them?

WHAT DID I ACTUALLY DO?

This is an obvious question, although perhaps not particularly important. After all, the solution is a very specific reflection of context, and personal attitudes and beliefs.

Having acquired an authentic gate, it seemed reasonable to retain something, and the vertical planking was the obvious element. I removed the rotting frame and built a new one, using pressure-treated wood and a prefabricated steel gate frame. I used a wood-epoxy mix to build up the missing end pieces of the boards. I replaced the splines between the boards with pieces cut from plastic political lawn signs. Most buildings do have stories to tell: sometimes the journey through time is more revealing than what was done originally. In another hundred years, when someone again considers the gate, they will remark on the fact that the different parts are of different times, and reflect different technologies and economics.

Of course, the finial of the gate is arbitrary. Down the street, they built a rather flamboyant top, following what the carpenter might have done originally. I chose a simpler design.

WHAT DID WE GET OUT OF IT?

How is value formed? This is an enigma, and answers do not come easily. Heritage matters frequently come into conflict with the goals and ambitions of designers, developers, marketing people and managers. Few people would suggest that heritage matters are unimportant and that there is no value associated with them. Yet, often decent debate is smothered by accusations of people proposing alternative approaches being scoundrels (it has happened to me).

I certainly have had benefits from the gate project. I have given a few lectures about it. It has been a wonderful conversation piece with our neighbours, and has positioned me locally as someone who values and respects heritage – not all of them know about the plastic bits.

There was probably no real economic value created through my decisions. Nicholson & Macbeth fanaticism infects few people. When we bought the house, its provenance was not even mentioned.

Perhaps just the thought processes involved in the gate are what are important in devising an appropriate design response, because they are much the same as those faced by people dealing with whole buildings and urban areas. Curiously, having done it, I recognize that, on one level, I would have preferred one of the original Nicholson & Macbeth designs, but there is still something special about having those authentic historic molecules.

· Originally published in OAA Perspectives. Vol.22, No.4, Winter 2014/15, pp.27-29.